Peer Reviewed Articles on College Age Students Nutritional Needs

- Research article

- Open Admission

- Published:

Determinants of eating behaviour in university students: a qualitative study using focus group discussions

BMC Public Health volume fourteen, Article number:53 (2014) Cite this commodity

Abstruse

Background

College or university is a disquisitional menses regarding unhealthy changes in eating behaviours in students. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore which factors influence Belgian (European) university students' eating behaviour, using a qualitative inquiry blueprint. Furthermore, we aimed to collect ideas and recommendations in club to facilitate the development of constructive and tailored intervention programs aiming to better healthy eating behaviours in university students.

Methods

Using a semi-structured question guide, five focus grouping discussions have been conducted consisting of xiv male person and 21 female person university students from a variety of report disciplines, with a mean historic period of 20.six ± 1.vii yrs. Using Nvivo9, an inductive thematic approach was used for data analysis.

Results

After the transition from secondary schoolhouse to university, when independency increases, students are continuously challenged to brand healthful food choices. Students reported to be influenced by individual factors (e.g. sense of taste preferences, cocky-subject, time and convenience), their social networks (east.one thousand. (lack of) parental command, friends and peers), physical surroundings (e.thousand. availability and accessibility, appeal and prices of food products), and macro environment (e.thousand. media and advertising). Furthermore, the relationships between determinants and university students' eating behaviour seemed to exist moderated by academy characteristics, such as residency, student societies, university lifestyle and exams. Recommendations for university administrators and researchers include providing information and communication to enhance good for you food choices and grooming (e.grand. via social media), enhancing self-discipline and self-control, developing time management skills, enhancing social support, and modifying the subjective also as the objective campus food environment by e.k. making healthy foods toll-benign and by providing vending machines with more healthy products.

Conclusions

This is the commencement European study examining perceived determinants of eating behaviour in university students and collecting ideas and recommendations for healthy eating interventions in a academy specific setting. University characteristics (residency, exams, etc.) influence the relationships between individual as well as social environmental determinants and university students' eating behaviour, and should therefore be taken into account when designing constructive and tailored multilevel intervention programs aiming to improve healthy eating behaviours in academy students.

Background

Prevention of overweight and obesity, and its related diseases [1], has become a worldwide challenge [ii]. According to U.s.a. literature, university is a critical period for weight proceeds [3–5]. During the transition from secondary school to university, students need to adapt to a new environment [vi, 7]. When students fail to accommodate fairly this could have negative consequences towards their health behaviours and subsequent weight condition [seven]. Eating behaviour (next to physical activity and sedentary behaviour) is an important factor influencing students' weight. According to studies conducted in US universities, students were not eating the recommended corporeality of fruit and vegetables, and were consuming increasing amounts of high-fat foods [8–10]. Furthermore, Butler et al. [9] reported meaning decreases in the amount of bread and vegetables consumed during the first year of university and significant increases in percentage fat intake and alcohol consumption in U.s. students. Unhealthy eating and excessive alcohol consumption may contribute significantly to free energy intake and may therefore facilitate student weight gain [11]. The same blueprint of weight gain in university students is emerging in Europe [12]. However, European literature on dietary intake in university students is scarce. In a Greek study [xiii] university students showed significantly college intake of total and saturated fat and lower intake of poly and monounsaturated fat, folate, vitamin E and fibre, compared to the American Heart Association guidelines. Crombie et al. [three] warned that these health behaviours may not only occur during the years at academy but may remain throughout adulthood every bit well. Therefore, prevention programs countering unhealthy eating habits in university students are needed, in order to foreclose an increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in later life.

To develop effective obesity prevention strategies it is of import to go insight into factors influencing eating behaviours in academy students. Early on theories explaining health behaviour generally focused on the individual inside its social context [xiv, 15]. According to Ajzen's Theory of Planned Behaviour [xiv], behaviour can be explained through intention. These intentions are being adamant by attitudes toward the behaviour, social or subjective norms and perceived behavioural control [14]. The Social Cognitive Theory of Bandura [15] on the other mitt, focuses on the interaction between personal (self-efficacy), behavioural (expected result) and social (modelling and social support) factors to explain health behaviours such as eating behaviour. Next to these psychosocial determinants, many researchers [16–eighteen] are convinced of the uttermost importance of the environmental influence on eating behaviours. According to Brug et al. [16] the environment has manifestly changed during the final decades, whereas opportunities to consume energy-dense foods are omnipresent. Egger et al. [17] suggested that the increasing obesogenic environment is the driving strength for the increasing prevalence of obesity rather than any 'pathology' in metabolic defects or genetic mutations inside individuals. Individuals collaborate in a variety of micro-environments or settings (e.grand. schools, workplaces, homes, (fast food) restaurants) which, in plough, are influenced by the macro-environments or sectors (e.g. food industry, authorities, society'southward attitudes and behavior) [18]. Ecological models consider the connections and the continuous interactions between people (intrapersonal) and their (sociocultural, policy and physical) environments [19–21]. Based upon the latter two theories Story et al. [19] proposed a framework including private (intrapersonal), social (interpersonal) ecology, concrete environmental and macro levels, to empathize factors influencing eating behaviours.

Only few qualitative studies, using focus group discussions, have examined determinants of eating behaviour in university students. Lack of field of study and fourth dimension, cocky-control, social support, production prices (costs) and limited budgets, and the availability of and access to (healthy) food options were reported equally of import influencing factors of students' eating behaviours [22–25]. All of these studies were conducted in the The states and either not included students of all report disciplines [22, 23] or did not specify students' study backgrounds [24, 25]. In addition, all studies included predominantly freshman students. However, including students of all report disciplines equally well as students with more academy experience (i.eastward. older students) could contribute to a wider range of experiences and opinions. Furthermore, no previous studies have included questions asking for recommendations towards intervention strategies aiming to improve good for you eating behaviours in academy students. To the best of our knowledge, no European (qualitative or quantitative) studies on determinants of eating behaviour in university students have been conducted so far. Many differences in lifestyle, environment and culture (e.g. fast food culture) tin can be observed between North-American and European students. Continental differences equally such might not only influence students' eating behaviour just also the enablers and barriers to engage in healthy eating practices. Hence, there is a need for European studies investigating determinants of eating behaviour in university students. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore which factors influence Belgian (European) university students' eating (incl. drinking) behaviour, using a qualitative research design. Furthermore, nosotros aimed to collect ideas and recommendations in order to facilitate the development of effective and tailored intervention programs aiming to amend healthy eating (incl. drinking) behaviours in university students.

Methods

Participants

In this qualitative written report focus group discussions were used for data drove. To ensure sufficient diversity of stance, students from the second till 5th year of university from unlike report disciplines were recruited using snowball sampling, a purposive nonprobability approach that is often used in qualitative research and in which the researcher recruits a few volunteers who, on their turn, recruit other volunteers. No first twelvemonth students were included because of their 'limited' experience every bit a academy student. The aim was to recruit betwixt 6 and ten participants per focus group [26]. An over-recruitment of one or 2 participants was pursued in case at that place were 'no-shows'.

Procedure

Focus groups were held until saturation of new information was reached, as in qualitative research sample size tin can never be pre-adamant [26]. To be sure we did not miss any 'new' data, 1 additional focus group session was held after theoretical saturation was estimated. All focus groups were organised at the Kinesthesia of Physical Education and Physiotherapy of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Brussels, Belgium) at a time and appointment convenient for the students and researchers. Earlier each focus group all participants were asked to complete a short questionnaire, including demographics, height, weight and perceived health (see Table i). Furthermore, caption almost the aim of the study was given and an informed consent (in which participants' anonymity and confidentiality were assured) was signed by each participant. Each focus group lasted between 90 and 120 minutes (including questions virtually concrete activeness and sedentary behaviour which were non included in this paper) and was facilitated by a moderator and an assistant moderator (observer), who took notes during the discussions and made sure the moderator did not overlook any participants trying to add comments. All focus group discussions were audiotaped with permission of the participants. Drinks and snacks were provided during the focus grouping discussions. Afterward, all students received an incentive (a tiffin voucher). The study was canonical by the Medical Ethical Commission of the university hospital.

Question guide

According to recommended focus group methodology [27], a semi-structured question guide (see Tabular array 2) was developed by the research squad, aiming to place factors influencing university students' health and weight related behaviours (including eating (and drinking) behaviour, physical activity and sedentary behaviour). As mentioned before, this paper will just focus on determinants of students' eating behaviour. Subsequently intensive collaboration with experts with ample focus group experience, the questions were carefully adult using appropriate literature [27]. When development was completed, the question guide was tested within and revised by the research team also equally pilot-tested in a group of x university students. Considering no major changes had to be made, 'airplane pilot' give-and-take results were included in later on assay [26]. The question guide consisted of opening and introductory questions which allowed participants to get acquainted and experience connected, and to start the give-and-take of the topic. Transition and primal questions were used to, respectively, guide the group towards the principal part of the discussion and to focus on the purpose of this study, i.eastward. identifying factors influencing students' eating behaviour. For obvious reasons, the greatest share of the group discussions focused on the key questions. Finally, students were asked to share ideas concerning health promotion equally well equally intervention strategies to counter unhealthy eating behaviours in university students. During the focus grouping discussions the moderator followed the question guide only asked side questions to obtain more than in-depth information about the topics, and showed enough flexibility to permit open up discussions between students.

Data analysis

SPSS Statistics 20 was used to analyse data obtained from the questionnaire and to calculate descriptive statistics of the focus group sample. Information obtained from the audio tapes where transcribed verbatim in Microsoft Discussion using Express Scribe and Windows Media Histrion. All quotes were encoded using the qualitative software plan Nvivo9. Using an inductive thematic approach, data (quotes) were examined for recurrent instances of some kind, which were then systematically identified beyond the information set, and grouped together by means of a coding arrangement (= content analysis) [28]. Similar codes were grouped together into more general concepts (subcategories) and further categorised into main categories. To ensure reliability of data interpretations, analyses were carried out independently by two researchers. Doubts or disagreements were discussed with 2 other researchers until consensus was reached.

Results

In this study, the estimated point of saturation was observed after the 4th focus group session. One additional focus group discussion was conducted to be certain true saturation was established. In total, 5 focus grouping discussions take been conducted, consisting of five to ten participants per grouping. The sample (due north = 35) consisted of fourteen male and 21 female students with a mean age of 20.6 ± 1.7 yrs (range = 18-26 yrs) and a mean study career of 3.0 ± 1.0 yrs. The majority of students (62.9%) were enrolled in man sciences, whereas respectively 17.1% and 20.0% were enrolled in exact and applied, and biomedical sciences. Additional sample characteristics are described in Table 1.

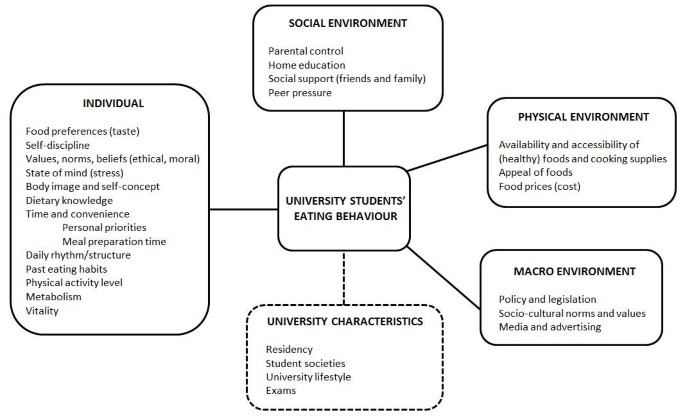

Co-ordinate to the ecological principles a framework of factors influencing eating (incl. drinking) behaviours in university students was adult based on content assay of the focus group discussions (Figure ane). The framework consists of four major levels, i.e. individual (intrapersonal), social environment (interpersonal), physical surroundings (customs settings), macro surroundings, and an boosted level of academy characteristics. The nigh appropriate quotes were chosen to illustrate each (sub)category.

Factors influencing eating behaviours of academy students.

Individual (intrapersonal)

Nutrient preferences (gustation)

Students reported that 'taste' is an important cistron influencing their nutrient choices. Gustatory modality tin make students swallow unhealthy, however it can help them brand healthy choices equally well: "I choose to swallow fruit because I similar fruit".

Cocky-discipline

Students believed that self-subject is related to self-dependency (autonomy) and may have an influence on their eating behaviour: "I do think that self-discipline is an of import factor (regarding eating behaviour) when you become self-dependent" (…) "You take to take care of yourself; some tin and others can't".

Values, norms, beliefs (ethical, moral)

According to the participants, norms and values as well as personal beliefs can influence students' eating behaviours. One educatee explained that moral conviction had driven him to become a vegetarian: "From the moment I became a vegetarian, it was so obvious for me that I didn't have the need to eat meat anymore (…) Yes, this was a moral conviction and I didn't take to have subject for it because it seemed obvious to me". Students likewise explained that they sometimes changed their eating behaviours due to a feeling of guilt when eating unhealthy foods such every bit pizza.

Country of heed (stress)

Students experienced the transition from secondary school to university as a stressful period. Participants also revealed that exam periods (when academic achievement pressure is highest) provide a lot of stress. Participants strongly believed that eating choices during stressful periods can be influenced in both directions. Some tend to consume healthier: "I eat more during test periods, but I tend to consume more fruits and vegetables". Others' eating patterns tend to worsen when experiencing such 'high' stress levels: "During test periods I can eat 'everything'; I'm always hungry". Non simply academic stress, but also social stress can modify students' eating behaviours: "Yes, when you don't feel well, eastward.m. heart broken, then the cliche of eating ice foam in forepart of the television becomes reality".

Body prototype and self-concept

Students spoke about their own trunk image and how it can have an effect on their eating behaviours. "When you don't find yourself attractive, consequently you call up others will think the same. That's a brutal circumvolve and it keeps getting worse and worse. And this tin can influence someone'due south eating behaviour." Students felt that body epitome is related to the socio-cultural platonic paradigm and is, in plow, related to media advert strategies.

Dietary knowledge

Participants believed that a certain dietary knowledge is needed to be able to brand changes in ane's eating blueprint. To a certain extent students seemed to exist aware of what is good for their health: "Actually, I don't like vegetables, simply I know that I need information technology and that's why I eat vegetables". However, they also stated that knowledge is just a start step and will not automatically pb to healthier nutrient choices. "When I would follow a health class tomorrow, it doesn't necessarily mean I would all of a sudden change my eating behaviour."

Time and convenience

Time seems to exist a very precious issue when talking about student eating practices. Students indicated they would rather spend time on other activities than cooking, especially when they take to melt but for themselves. Participants best-selling that 'time' is a relative term and it is oft related to personal priorities: "Because here on campus (when living in a student residence) I always take something else to do instead of cooking, then I don't have time to make dinner". Students explained that repast preparation time is of cracking importance: "The faster my meal is gear up, the better, so I can install myself in front end of the goggle box". According to the students easiness and convenience, which is related to time, is an of import factor as well: "I want it to be easy, so I don't accept to exist cooking for one hr for myself, …, so I grab something that can be warmed up apace". Time is mentioned to exist particularly of import during exam periods: "After exam periods, you accept more time to cook. When you are studying (during exam periods), yous want to spend as little time as possible on cooking".

Daily rhythm/structure

Students indicated that many students alive a rather unstructured life (incl. sleeping habits), especially when living in student residences. Hence, their eating practices tin can suffer from this. "When you stay awake longer, the urge to grab something sweetness (cookies, candy, …) is bigger, whilst when having a skillful sleeping pattern, the urge may be smaller." On the other hand, when living with their parents, students felt they were subject to a certain 'structure'. "When I lived at home, everything was nicely structured and I didn't even have to think most information technology, because the foundations had already been set by my parents."

By eating habits

Participants felt they had regular eating habits. According to the students these eating practices are a event of eating habits created during babyhood and boyhood: "My salubrious habits didn't modify by living abroad from home (in a student residence), because already all my life I drink i.v litres of water per day and I still practice. I almost never drink Coca Cola."

Physical action level

Students stated that a higher caloric intake is needed when exercising: "I didn't feel safe anymore when playing rugby, then I started eating more than; more carbohydrates etc., and then I pay attending to what I eat". Also, information technology was mentioned that some students tend to call back they tin can eat anything they want after exercising: "Some think that later they have exercised, they can swallow a hamburger".

Metabolism

Students suggested that metabolism can differ between 1 another. Some students tend to 'burn' calories more easily than others. "(1 of the students towards a student colleague:) Your metabolism is abnormal, you eat and yous potable what you lot want and you don't gain weight."

Vitality

It was mentioned that when being tired, students tend to consume more energy-dense foods: "When you are more tired the urge for sugars is bigger because you want to drag your energy level". However, lack of vitality could also trigger some kind of health sensation: "I noticed that in my first twelvemonth at university I didn't eat vegetables sufficiently and I felt tired and didn't have enough energy. Therefore, I started eating vegetables and fruit. Consequently, I had lots more energy …"

Social environment (interpersonal)

Parental command

Students felt that parental control had a crucial role in their eating behaviours. When parental control is lacking this tin can have great influences on individual food choices. "Afterward the transition from secondary school to academy, parental control decreased, so consequently 'freedom' increased, which means you become more self-dependent and that has influenced my eating behaviour. For example, in secondary school you lot had habitation prepared sandwiches for dejeuner, while at academy y'all can eat cafeteria sandwiches and dessert etc." Moreover, alcohol consumption was described to be more common when parental control is lacking: "In pupil residences it is easier to play drinking games, because your parents cannot see what you're doing".

Home didactics

Students indicated that eating habits may depend on their abode education. When ane is raised in a more healthy environs it is more probable ane consumes east.g. sufficient fruits and vegetables. "My mother fabricated me consume my vegetables, fifty-fifty though I didn't similar to."

Social support (friends and family)

Students revealed that support from family and friends can influence their eating behaviour: "During exam periods I am happy that mom prepares my meal, considering if I had to make it all by myself, I would make pizza more often". Living together with peers can also influence eating behaviours: "I alive together with my girlfriend, but when I would alive all by myself, I would pay less attention to what I eat". Students emphasized the importance of a great social supporting network: "When you lot take no friends, you tin can't bargain with 'stressy' events properly which tin can accept direct consequences on your personal health".

Peer pressure

Group or peer pressure was explained to be an influencing gene of individual food choices. "You can make your own sandwiches, simply then you might be the only one in the grouping, so the next day chances are large you likewise buy a sandwich on campus."

Physical environment (community settings)

Availability and accessibility of (salubrious) foods and cooking supplies

When students take easy access to (on-campus) eating facilities, they seem to get tempted more easily. For case, the student eating place and its meal offers seem to influence students regarding their individual nutrient choices. "In the student restaurant y'all tin can cull every twenty-four hours between French fries, (mashed) potatoes or rice. I think lots of students tend to take French chips every time." On the other hand students expressed that the academy eating house offers a lot of meal choices and it depends on the individual whether good for you or less salubrious choices are beingness made. "I think we cannot mutter of what is offered in the student eatery. There is plenty variety." Participants too mentioned the presence of numerous candy machines on campus which might be of influence as well. On the other hand they mentioned that when healthy foods are available in their nearest environment, and certainly when it'due south for gratuitous, they tend to swallow more than good for you alternatives. "During exam periods free fruit was available in the university's study hall and afterwards you could notice an increase of fruit consumption." Moreover, living in a student residence, where the availability of cooking supplies is ofttimes limited, can influence meal choices besides: "Non all educatee residences have a fully equipped kitchen" (…) "Since I don't have a fryer (in the student residence) I tin can't fix anything fried, then I mostly eat more healthy foods". Students too believed that a lack of cooking supplies could contribute to more unhealthy food choices.

Appeal of foods

Students believed that the entreatment of food items makes it sometimes hard for them to make salubrious choices. "Indeed, the (student) restaurant is a 'dangerous' place, you walk into the bottle and you lot run across others (friends) eating lasagne and subsequently you lot leave your sandwiches in your bag and go get some lasagne likewise. In contrast to secondary school, you get tempted more speedily at present."

Food prices (cost)

Food product prices and individual upkeep influence students' food choices. On the 1 paw, when eating outdoors, they might spend more money: "If I'd buy a sandwich every day it would go too expensive. I live currently by myself and it (money/price) becomes more than important, and then I have to pay attention and eat my habitation prepared and healthier sandwiches". On the other manus, students besides believed that unhealthier foods in due east.g. fast nutrient restaurants are less expensive than preparing a healthy meal at home. "It will exist more expensive when you swallow good for you; for instance a lasagne is cheaper than buying leek, onions and carrots." Students referred to the American eating civilisation: "I call up that unhealthy foods are cheaper than salubrious foods. Just look at the 'i dollar menus' in the U.s.; this is a big problem (regarding public wellness)". In contrast, others believed that this is non e'er truthful. "Some vegetables and fruits are cheaper than sure cookies. So, that'southward also ane of the reasons why I sometimes purchase apples (instead of cookies); because it'due south cheaper." Participants likewise mentioned that when living in a student residence, one becomes more self-dependent which also implies that toll and budget become more and more than important. "When yous live in a student residence, y'all have to purchase your ain food, and so you automatically start to pay attention to product prices."

Macro surroundings

Policy and legislation

Students recognised that they are restricted by policy and legislation which influence their drinking choices. East.g. alcohol consumption can be influenced by governmental regulations: "When you get out by automobile, you are non allowed to drink and drive, so you volition automatically drink less, … much less".

Socio-cultural norms and values

Students mentioned that certain eating behaviours can be region as well as society specific: "Only this (eating behaviour) is specific to our order; nowadays, when yous expect at the United states of america, for them it is normal to get eat fast food every day, whilst here in Europe information technology isn't". These socio-cultural norms practise not only differ geographically, merely tin can modify over time every bit well: "Our civilisation has evolved as such that alcohol has get a socially accepted drug".

Media and advertising

Participants felt influenced by media and advert: "When I encounter nutrient on tv set, I am more likely to go get something from the cupboard; on the 1 mitt because I feel similar information technology, only likewise considering I see information technology on telly".

Academy characteristics

Residency

Participants felt that students living in a pupil residence and being surrounded by other student peers are often bailiwick to lots of stimuli influencing their eating behaviour. "Yous see a lot of students who but arrived at university and stay in a student residence, eating lasagne, or pizza, …" (…) "I noticed that students living in pupil residences eat much more than unhealthy foods, become out more and drink more …" One students' personal feel confirmed the latter: "I have lived in a student residence for four years and I gained x kg of weight because of going out too much and eating unhealthy". Notwithstanding, other participants reported no changes in eating behaviour: "I already live two years in a student residence and I don't have the impression that my habits take inverse, I nevertheless eat healthy". The educatee environment can take a positive influence on eating behaviour also. Students expressed that when living in a student residence and cooking together (with peers) they accept their time to set a meal which enlarges the chances of making a 'healthy' meal.

Pupil societies

Student societies influence students' drinking habits: "When you lot go out with other pupil society members, you are almost obliged to potable (alcohol)".

University lifestyle

Students explained that the excitement and novelty when arriving at university can cause students to become out more and 'gustation' the university life. They also believed start yr students arriving at university can be very influenceable: "Many people I had never seen drinking before started drinking at academy". Furthermore, one of the students explained how life at the university influenced her eating and drinking behaviour: "When I arrived at academy, I was a superlative athlete (pond) and I had a very salubrious lifestyle back and so. When I quit (swimming) I practically lived on campus, so every night I went to parties and drank and ate a lot and my torso experienced these changes. After my sporting career I 'discovered the world' (in terms of drinking, eating, friends, …) but at present it has stabilised".

Exams

Participants reported that eating behaviours during the academic year can differ (in a positive and a negative fashion) from those during examination periods: "During examination periods I gain weight, because I tend to speedily take hold of something during a break". In contrast, one of the students replied every bit follows: "I eat healthier (during exam periods) to maintain my personal health, and I slumber more equally well".

Suggestions for interventions

Private level

Participants believed that direct (one-on-one) communication should exist used. "Yous have to confront students individually (to sensitize), because 'general' promotion is not as effective (…) Giving students personal feedback on their health status volition exist more effective." Nevertheless, 1 student suggested to use posters: "I think using posters displaying e.one thousand. the 'good for you eating pyramid' will not stay unnoticed". Furthermore information technology was mentioned that "all students should be given similar one hour of data (most healthy eating) by means of a health class". However, one of the students mentioned that "noesis helps you lot to make decisions, just it doesn't strength you". Students too thought it was important to give advice via internet and social media: "… like Facebook, you can check your messages whenever you desire and you are costless to choose whether you read it or not". Furthermore, participants believed that promotion strategies should focus on convenience: "Promotion strategies should be 'easy going' and convenient, don't make it look like students have to exercise a lot of attempt to be healthy".

Environmental level

When request participants for suggestions regarding intervention development, students believed that the educatee restaurant could provide more healthy menus: "The student eating place should offer more than healthy carte choices, and then you actually oblige students subtly to consume good for you" (…) "Information technology would be good when, for example, they (the pupil eating house) wouldn't always offer French chips, because (when bachelor) I tend to choose French fries very ofttimes". Concerning price and toll, it was also mentioned that "the pupil eating house should change its prices, because that would motivate students to eat more than healthy foods when lower in price" (…) "Students will choose a salubrious card (due east.yard. vegetarian pasta) lower in price over a less salubrious and more than expensive ane (e.g. steak). At to the lowest degree, I know I would, although unremarkably, I would rather eat meat". Participants also expressed that "they (the government) should implement higher taxes for unhealthy (e.g. loftier-fat) foods". Another suggestion was to brandish the corporeality of calories on every menu. "When the student eatery would display calories, lots of students will probably think twice when choosing a dish." Students also felt that campus vending machines should comprise more healthy products: "The on-campus vending machines are not healthy" (…) "In secondary school, they replaced all vending automobile products by healthy foods and it led to lower consumption of vending products, but as well, students were obliged to choose a good for you production".

Discussion

The purpose of this explorative study was to identify determinants of eating (incl. drinking) behaviours in Belgian (European) university students. Furthermore, we aimed to collect ideas and recommendations in order to facilitate the development of effective and tailored intervention programs aiming to improve good for you eating (incl. drinking) behaviours in university students. Like to Story'south framework [nineteen] combining Bandura's Social Cerebral Theory [15] with Sallis' ecological model [21] explaining health behaviour, we identified four major levels of determinants: individual (intrapersonal), social surroundings (interpersonal), physical environment (community settings) and macro environment (societal). Furthermore, some university specific characteristics were found to be influencing students' eating behaviours as well.

Similar to Us literature [22–25], many cocky-regulatory processes, including intrinsic (east.g. food preferences) and extrinsic (e.g. health sensation, guilt) motivations, self-discipline, self-command, time management, etc. accept been mentioned by our participants to be influencing eating behaviour in university students. Our results further betoken that these latter determinants become more than important after the transition from secondary school to university when independency subsequently increases. In a qualitative study of Cluskey et al. [25], university students who reported greater independency and more responsibility for nutrient and meal preparation prior to college, felt to have achieved more stability in their eating behaviours at college. Therefore, LaCaille et al. [23] suggested that future interventions should aim at strengthening students' self-regulation skills around eating as function of the overall transition to university or college. Such self-regulation and self-management skills can aid students to make more healthy decisions and to maintain a healthful lifestyle throughout adulthood [24]. Moreover, the systematic review of Kelly et al. [29] evaluating the effectiveness of dietary interventions in higher students suggested that approaches involving self-regulation strategies take the potential to facilitate changes in students' dietary intake.

Although in the study of Cluskey et al. [25] US students most agreed that intrinsic motivation was needed for successful changes in healthful behaviour, our results indicate that the environs should be organised as such, 'forcing' students to make healthful food choices. Students' nutrient choices are influenced by the availability and accessibility of healthy foods and cooking supplies [22]. Therefore, our participants suggested that offering more healthy menus in the student eating place as well equally providing campus vending machines with more healthy products could contribute to making more healthful food choices. Information technology has been shown that food availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables is strongly and positively related to fruit and vegetable consumption in children [30]. In addition, students in the current written report mentioned that the entreatment of (on-campus) foods ofttimes determines food choices. This suggests that making healthy products offered effectually campus more appealing might contribute to more healthy eating behaviours in university students.

Students in the current study believed they are continuously challenged by competing demands, including bookish responsibilities and interest in extracurricular and social activities. As mentioned by Nelson et al. [24], healthy nutrient choices may become low priorities when compared to other commitments. Therefore, every bit described by our participants, students might be more than likely to buy foods that are fast, convenient and inexpensive. Marquis et al. [31] showed that college students oftentimes prioritize cost and convenience over health. Moreover, previous studies establish that toll is one of the most influential individual factors (next to taste) in determining nutrient choice in both adults and adolescents [32–36]. In our study, participants felt that offering more than healthy (on campus) foods at a lower cost would contribute to more than healthful food choices. Intervention studies in other populations have shown that cost reductions increase purchases of lower-fat products and fruits and vegetables in cafeterias, workplaces and school vending machines [34, 36]. Given the importance of toll in university students' nutrient choices, this might even be a more than effective strategy in this population.

Similar to previous research in adolescents [37], participants felt that perceived benefits (e.g. improving wellness status, higher vitality) of healthful eating behaviour can influence food choices likewise. Students also believed that dietary knowledge should be a first step towards the awareness on healthy eating behaviour. Cluskey et al. [25] mentioned that academy students lack the noesis and skills to make healthful food choices as well as to prepare healthy foods, which makes information technology difficult to adjust healthfully to college or academy life. Information technology was suggested by our participants that all students should exist given a health education course.

In this report, students mentioned that parents and household influence their nutrient intake. A review study on environmental influences on nutrient choices [38] indicated that adolescents' dietary intake is being influenced by their family members. Parents serve as models for eating behaviour and transmit dietary attitudes throughout the upbringing of their offspring [38]. The latter suggests that peculiarly academy students living with their parents might experience similar parental influences. As well family unit influences, our participants believed that friends and peers influence their eating behaviour as well. Contento et al. [39] reported that attitudes, encouragement, and behaviours of friends and peers influenced adolescents' food choices. In a natural experiment assessing peer effects on weight, information technology was shown that the amount of weight gained during the freshman year was strongly and negatively correlated to the roommate'south initial weight [40], suggesting that peers are influenced by each other's eating behaviours.

Living arrangements (residency) and exams were mentioned to be influencing students' eating behaviours. Information technology has been shown that living arrangements tin can affect university students' dietary intake [41–43]. In a study in four European countries students living at parental home consumed more fruit and vegetables than those who resided outside of their family home [43]. In addition, in a natural experiment, Kapinos et al. [44] showed that students assigned to dormitories with on-site dining halls gained more than weight and exhibited more behaviours consequent with weight gain (e.g. males consumed more meals and snacks) during the freshman twelvemonth as compared with students not assigned to such dormitories. Living arrangements might be moderating the relation betwixt eating behaviour and its determinants rather than causing eating behaviour as such. According to MacKinnon [45], a moderator affects the forcefulness of the relation between two variables. E.one thousand. living in a student residence may moderate the relation between parental influence and eating behaviour, i.e. parental control volition decrease when students live away from abode. Results of the current report suggest that the relation between parental control and eating behaviour might exist stronger in students living at home compared to those living abroad from home. Also, when living in a educatee residence (and receiving a weekly based allowance) our results revealed that food prices become more important when making food choices, i.e. students have to pay attention to 'what' they purchase. Thus, a stronger relationship between food prices and eating behaviour might be observed when students live away from home in comparing to those living with their parents. Exams can have a similar moderating result on the relation between eastward.yard. time and eating behaviour. Our results testify that during exam periods students will spend every bit little time equally possible on cooking.

When comparing with the limited U.s.a. literature, it should be noticed that, despite similarities betwixt this report and other US studies (eastward.m. lack of time, unorganised living), some determinants tin can be region or culture-specific. For instance, students in the nowadays study referred to the arable availability of fast food and one-dollar-menus in the US, in comparison to Europe. Focus group discussions with US university students pointed out that all-you-can-eat formulas of on-campus dining facilities had a negative impact on their healthy eating behaviours [23, 25]. In contrast to US universities our universities exercise not dispose of all-you lot-can-eat dining possibilities. Furthermore, unlike Usa colleges/universities, Belgian universities do non have on-campus dormitory dining halls where campus meal plans for students are provided.

Our results also indicate that what may be a barrier for one student may be perceived as an enabler by another. For example, with regard to the physical campus environment, some students felt that the pupil restaurant was a barrier to healthful eating behaviour, whereas others believed it enabled students to make healthy food choices. Therefore, with regard to hereafter intervention programs, nosotros should alter perceptions of physical environs as well, rather than the objective environment on its ain.

Furthermore, our results indicate that concrete and social environments are continuously interacting with self-regulatory processes and thus individual eating behaviours. Information technology could exist that a certain stimulation at the private level might not exist irresolute i'southward eating behaviour when acting in a non-benign social and/or concrete environment, and vice versa. Therefore, intervention strategies based on multilevel approaches may be most effective [21].

This qualitative research methodology, using focus groups, is an important strength of this explorative study. As Sallis et al. [46] suggested, qualitative research allows us to understand not simply the 'what' just likewise the 'how' and 'why'. Using an inductive thematic methodology allowed the research team to construct a pupil-specific framework. Furthermore, in contrast to in-depth interviews, the more 'naturalistic' approach (i.e. closer to everyday conversation), including dynamic group interaction [28], immune united states of america to get better insight into the mechanisms behind academy students' eating behaviours. On the other hand, some participants might have been intimidated past the group setting which might take limited a greater sharing of their thoughts.

A first limitation of this written report is that nosotros used educatee volunteers. We have to have into account that participants were probably interested in this topic, which might have resulted in a pick bias. However, sample characteristics showed sufficient diverseness in BMI and perceived health status. Secondly, whereas we might expect differences in behaviours according to gender [47] or year in schoolhouse, we chose to use mixed-gender focus groups including students of different report years and disciplines, allowing united states to create interaction between both genders with a diverseness of study experience and backgrounds, which in turn generated a greater diversity in opinion inside each focus group. Thirdly, focus groups were conducted at i university, which has a campus outside the city heart. Because of academy specific environmental differences (due east.chiliad. size, structure, region, etc.), the applicability of the study'due south findings to other pupil populations is limited to the psychosocial level, whereas futurity studies should further explore the physical environmental issues within a diverseness of other Belgian or European universities. Finally, because of the abovementioned setting limitation and the explorative nature of this study no conclusions can be drawn concerning the importance of each determinant and the generalizability of our results. The purpose of using focus groups is to generate a rich agreement of participants' experiences and behavior [48, 49] and non to generalize results [50]. In improver, no quantification was used because numbers and percentages convey the impression that results tin can be projected to a population, and this is not inside the capabilities of qualitative research [50]. Also, the issue raised about frequently is not necessarily the most of import, even when it is raised by a larger number of people [50]. In other words, each idea or opinion should exist as appreciated. Therefore, time to come studies, using a larger representative sample size, should focus on providing quantitative evidence regarding the importance and value of each determinant, making information technology also possible to differentiate according to gender, year in school, study discipline, or other student characteristics. After, future tailored interventions could focus on those factors students experience equally most determinative in their electric current eating behaviour.

Conclusions

To the best of our noesis, this is the starting time European study examining perceived determinants of eating (incl. drinking) behaviour in university students and collecting ideas and recommendations in order to facilitate the evolution of constructive and tailored intervention programs aiming to improve good for you eating (and drinking) behaviours in university students. An ecological framework of determinants of university students' eating behaviour was developed. Students were plant to be influenced by individual factors, their social networks, concrete environment, and macro environment. Furthermore, the relationships between determinants and university students' eating behaviour seemed to be moderated past university characteristics, such equally residency, student societies, university lifestyle and exams. After the transition from secondary school to academy, when independency increases, students are continuously challenged to brand healthful food choices. They accept to be self-disciplined, accept cocky-control and thus frequently have to prioritize healthy eating over other (academy specific) social activities in order to gear up a healthy repast. In improver, students have to make these healthful food choices within a university specific setting (e.g. living in a student residence, having exams), depending on the availability and accessibility, appeal and prices of nutrient products. Moreover, during this pick making process, students are either controlled or lacking control by their parents as well as influenced by friends and peers. Recommendations for academy administrators and researchers include providing information and communication to enhance healthy food choices and preparation (due east.one thousand. via social media), enhancing self-discipline and self-control, developing fourth dimension management skills, enhancing social support, and modifying the subjective as well equally the objective campus food environment by e.grand. making healthy foods price-benign and by providing vending machines with more healthy products. Our results should exist considered a first pace into the evolution of tailored and constructive intervention programs aiming to meliorate academy students' eating behaviours.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Trunk mass index

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- yrs:

-

Years.

References

-

Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai SF, Ford ES, Flim-flam CS, et al: Executive summary: eye illness and stroke statistics - 2012 update a report from the American Center Association. Apportionment. 2012, 125 (1): 188-197.

-

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM: Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among Us children and adolescents, 1999-2010. J Am Med Assoc. 2012, 307 (5): 483-490. x.1001/jama.2012.xl.

-

Crombie AP, Ilich JZ, Dutton GR, Panton LB, Abood DA: The freshman weight gain phenomenon revisited. Nutr Rev. 2009, 67 (ii): 83-94. ten.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00143.ten.

-

Vella-Zarb RA, Elgar FJ: The 'freshman 5': a meta-analysis of weight gain in the freshman year of college. J Am Coll Health. 2009, 58 (two): 161-166. ten.1080/07448480903221392.

-

Racette SB, Deusinger SS, Strube MJ, Highstein GR, Deusinger RH: Changes in weight and health behaviors from freshman through senior year of college. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008, 40 (1): 39-42. 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.01.001.

-

Dyson R, Renk 1000: Freshmen accommodation to academy life: depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. J Clin Psychol. 2006, 62 (x): 1231-1244. x.1002/jclp.20295.

-

Von Ah D, Ebert S, Ngamvitroj A, Park Due north, Kang DH: Predictors of health behaviours in college students. J Adv Nurs. 2004, 48 (5): 463-474. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03229.x.

-

Silliman Grand, Rodas-Fortier Yard, Neyman M: A survey of dietary and exercise habits and perceived barriers to post-obit a good for you lifestyle in a college population. Californian J Health Promot. 2004, 2 (two): 10-nineteen.

-

Butler SM, Black DR, Blue CL, Gretebeck RJ: Change in diet, physical activity, and torso weight in female college freshman. Am J Health Behav. 2004, 28 (1): 24-32. ten.5993/AJHB.28.1.3.

-

DeBate RD, Topping M, Sargent RG: Racial and gender differences in weight condition and dietary practices amidst college students. Adolescence. 2001, 36 (144): 819-833.

-

Lloyd-Richardson EE, Lucero ML, DiBello JR, Jacobson AE, Wing RR: The human relationship between alcohol use, eating habits and weight change in college freshmen. Eat Behav. 2008, 9: 504-508. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.06.005.

-

Deliens T, Clarys P, Van Hecke 50, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Deforche B: Changes in weight and body composition during the start semester at university. A prospective explanatory written report. Appetite. 2013, 65C: 111-116.

-

Chourdakis Thousand, Tzellos T, Pourzitaki C, Toulis KA, Papazisis G, Kouvelas D: Evaluation of dietary habits and assessment of cardiovascular disease risk factors among Greek academy students. Appetite. 2011, 57 (ii): 377-383. 10.1016/j.appet.2011.05.314.

-

Ajzen I: From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. 1985, Berlin: Springer

-

Bandura A: Social Foundations of Idea and Activeness: A Social Cognitive Theory. 1986, Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall

-

Brug J, van Lenthe FJ, Kremers SPJ: Revisiting Kurt Lewin - How to proceeds insight into environmental correlates of obesogenic behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 31 (6): 525-529. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.016.

-

Egger G, Swinburn B: An "ecological" approach to the obesity pandemic. BMJ. 1997, 315 (7106): 477-480. 10.1136/bmj.315.7106.477.

-

Swinburn BA, Caterson I, Seidell JC, James WP: Nutrition, nutrition and the prevention of excess weight gain and obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2004, vii (1A): 123-146.

-

Story G, Neumark-Sztainer D, French S: Individual and environmental influences on boyish eating behaviors. J Am Nutrition Assoc. 2002, 102 (iii): S40-S51. 10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90421-nine.

-

Biddle SJH, Mutrie N: Psychology of Concrete Activity: Determinants, Well-Being and Interventions. 2008, New York: Routledge, 2

-

Sallis JF, Owen Northward: Ecological Models of Health Behavior. 2002, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, three

-

Greaney ML, Less FD, White AA, Dayton SF, Riebe D, Blissmer B, Shoff S, Walsh JR, Greene GW: College Students' barriers and enablers for healthful weight direction: a qualitative study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009, 41 (4): 281-286. 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.04.354.

-

LaCaille LJ, Dauner KN, Krambeer RJ, Pedersen J: Psychosocial and environmental determinants of eating behaviors, concrete activity, and weight change among higher students: a qualitative analysis. J Am Coll Health. 2011, 59 (6): 531-538. 10.1080/07448481.2010.523855.

-

Nelson MC, Kocos R, Lytle LA, Perry CL: Agreement the perceived determinants of weight-related behaviors in tardily adolescence: a qualitative analysis among college youth. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009, 41 (4): 287-292. ten.1016/j.jneb.2008.05.005.

-

Cluskey M, Grobe D: College weight gain and behavior transitions: male and female differences. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009, 109 (2): 325-329. 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.045.

-

Morgan DL, Scannell AU: Planning Focus Groups. 1998, Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications

-

Krueger RA: Developing Questions for Focus Groups. 1998, G Oaks, California: Sage Publications

-

Silverman D: Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice. 2004, London, Chiliad Oaks, New Delhi: Sage Publications, Second

-

Kelly NR, Mazzeo SE, Bean MK: Systematic review of dietary interventions with college students: directions for future inquiry and practise. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013, 45 (4): 304-313. 10.1016/j.jneb.2012.x.012.

-

Hearn MD, Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Doyle C, Smith Chiliad, Lin LS, Resnicow Grand: Environmental influences on dietary behavior among children: availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables enable consumption. J Wellness Ed. 1998, 29: 26-32.

-

Marquis M: Exploring convenience orientation every bit a food motivation for college students living in residence halls. Int J Consum Stud. 2005, 29 (1): 55-63. 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2005.00375.x.

-

Shannon C, Story M, Fulkerson JA, French SA: Factors in the school deli influencing food choices by high school students. J Sch Health. 2002, 72 (6): 229-234. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb07335.x.

-

French SA, Story M, Hannan P, Breitlow KK, Jeffery RW, Baxter JS, Snyder MP: Cognitive and demographic correlates of low-fat vending snack choices among adolescents and adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999, 99 (iv): 471-475. 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00117-0.

-

French SA, Jeffery RW, Story K, Breitlow KK, Baxter JS, Hannan P, Snyder MP: Pricing and promotion effects on depression-fat vending snack purchases: the Fries study. Am J Public Health. 2001, 91 (ane): 112-117.

-

Glanz K, Basil M, Maibach Due east, Goldberg J, Snyder D: Why Americans swallow what they exercise: gustation, nutrition, cost, convenience, and weight control concerns equally influences on food consumption. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998, 98 (10): 1118-1126. 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00260-0.

-

French SA, Story Thousand, Jeffery RW, Snyder P, Eisenberg M, Sidebottom A, Murray D: Pricing strategy to promote fruit and vegetable purchase in loftier school cafeterias. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997, 97 (nine): 1008-1010. ten.1016/S0002-8223(97)00242-3.

-

Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C, Casey MA: Factors influencing food choices of adolescents: findings from focus-group discussions with adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999, 99 (8): 929-937. ten.1016/S0002-8223(99)00222-9.

-

Larson N, Story G: A review of environmental influences on food choices. Ann Behav Med. 2009, 38 (Suppl one): S56-S73.

-

Contento IR, Williams SS, Michela JL, Franklin AB: Understanding the food selection procedure of adolescents in the context of family and friends. J Adolescent Health. 2006, 38 (5): 575-582. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.025.

-

Yakusheva O, Kapinos One thousand, Weiss 1000: Peer furnishings and the freshman 15: evidence from a natural experiment. Econ Hum Biol. 2011, nine (two): 119-132. 10.1016/j.ehb.2010.12.002.

-

Brevard PB, Ricketts CD: Residence of college students affects dietary intake, concrete action, and serum lipid levels. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996, 96 (1): 35-38. x.1016/S0002-8223(96)00011-9.

-

Burden AR, Rhee YS: Obesity and lifestyle in US college students related to living arrangemeents. Appetite. 2008, 51 (iii): 615-621. 10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.019.

-

El Ansari W, Stock C, Mikolajczyk RT: Relationships betwixt food consumption and living arrangements among academy students in iv European countries - a cross-exclusive written report. Nutr J. 2012, 11: 28-10.1186/1475-2891-11-28.

-

Kapinos KA, Yakusheva O: Environmental influences on young developed weight gain: evidence from a natural experiment. J Adolescent Health. 2011, 48 (1): 52-58. x.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.05.021.

-

MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS: Mediation assay. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007, 58: 593-614. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542.

-

Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher West, Henderson KA, Kraft MK, Kerr J: An ecological arroyo to creating agile living communities. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006, 27: 297-322. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100.

-

Boek Due south, Bianco-Simeral Due south, Chan K, Goto K: Gender and race are significant determinants of students' nutrient choices on a college campus. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012, 44 (4): 372-378. ten.1016/j.jneb.2011.12.007.

-

Morgan DL: The Focus Group Guidebook. 1998, One thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications

-

Maxwell J: Qualitative Inquiry Design: An Interactive Approach. 2005, 1000 Oaks, CA: Sage, two

-

Krueger RA: Analyzing & Reporting Focus Group Results. 1998, 1000 Oaks, California: Sage Publications

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/53/prepub

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all students participating in this report. Special thanks to Pieter Van Der Veken for his contribution regarding data collection and transcription.

Writer information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TD participated in the blueprint of the study, collected all information, performed the data analyses and drafted the manuscript. IDB participated in the blueprint of the study and revised the manuscript critically. PC and BD participated in the design of the study, contributed to the estimation of data and revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published nether license to BioMed Key Ltd. This is an open admission article distributed nether the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original piece of work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this commodity

Deliens, T., Clarys, P., De Bourdeaudhuij, I. et al. Determinants of eating behaviour in university students: a qualitative written report using focus group discussions. BMC Public Health 14, 53 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-53

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-xiv-53

Keywords

- Determinants

- Eating behaviour

- University students

- Focus groups

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-14-53

0 Response to "Peer Reviewed Articles on College Age Students Nutritional Needs"

Post a Comment